Scaling Performance Comparison: ScyllaDB Tablets vs Cassandra vNodes

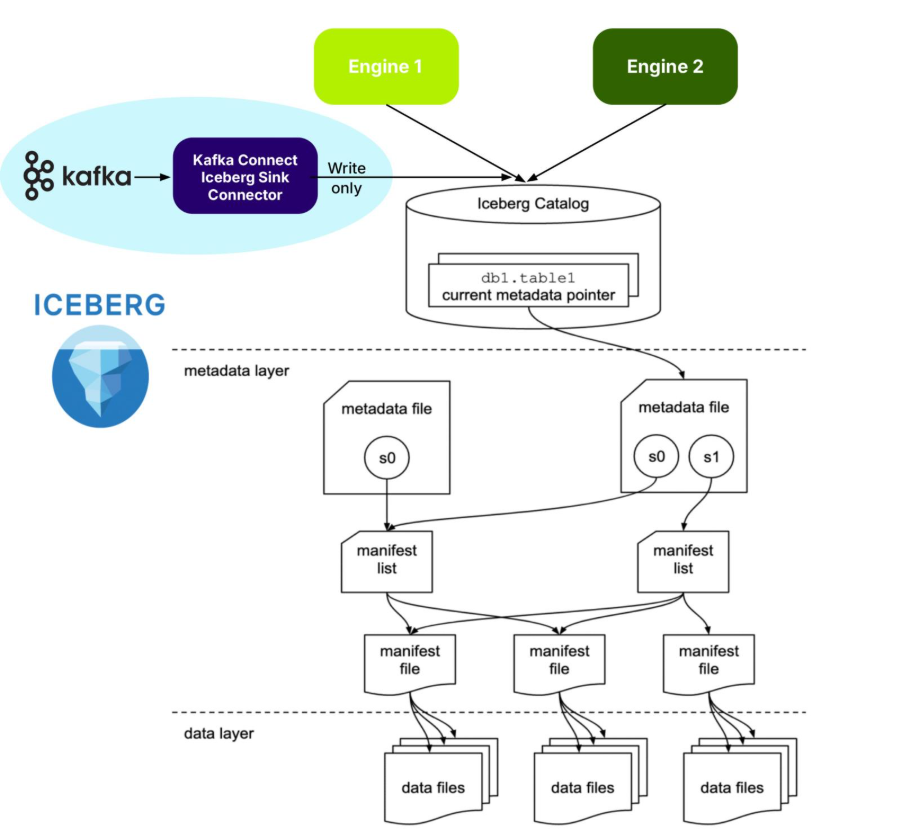

Benchmarks show ScyllaDB tablet-based scaling 7.2× faster than Cassandra’s vNode-based scaling (9× with cleanup), sustaining ~3.5X higher throughput with fewer errors Real-world database deployments rarely experience steady traffic. Systems need sufficient headroom to absorb short bursts, perform maintenance safely, and survive unexpected spikes. At the same time, permanently sizing for peak load is wasteful. Elasticity lets you handle fluctuations without running an overprovisioned cluster. Increase capacity just-in-time when needed, then scale back as soon as the peak passes. When we built ScyllaDB just over a decade ago, it scaled fast enough for user needs at the time. However, deployments grew larger and nodes stored far more data per vCPU. Streaming took longer, especially on complex schemas that required heavy CPU work to serialize and deserialize data. The leaderless design forced operators to serialize topology changes, preventing parallel bootstraps or decommissions. And static (vNode-based) token assignments also meant data couldn’t be moved dynamically once a node was added. ScyllaDB’s recent move to tablet-based data distribution was designed to address those elasticity constraints. ScyllaDB now organizes data into independent tablets that dynamically split or merge as data grows or shrinks. Instead of being fixed to static ranges, tablets are load balanced transparently in the background to maintain optimal distribution. Clusters scale quickly with demand, so teams don’t need to overprovision ahead of time. If load increases, multiple nodes can be bootstrapped in parallel and start serving traffic almost immediately. Tablets rebalance in small increments, letting teams safely use up to ~90% of available storage. This means less wasted storage. The goal of this design is to make data movement more granular and reduce the serialized steps that constrained vNode-based scaling. To understand the impact of this design shift, we evaluated how both ScyllaDB (now using tablets) and Cassandra (still using vNodes) compare when they must increase capacity under active traffic. The goal was to observe scale-out under realistic conditions: workloads running, caches warm, and topology changes occurring mid-operation. By expanding both clusters step by step, we captured how quickly capacity came online, how much the running workload was affected, and how each system performed after each expansion. Before we go deeper into the details, here are the key findings from the tests: Bootstrap operations: ScyllaDB completed capacity expansion 7.2X faster than Cassandra Total scaling time: When including Cassandra’s required cleanup operations (which can be performed during maintenance windows), the time difference reaches 9X Throughput while scaling: ScyllaDB sustained ~3.5X more traffic during these scaling operations Stability under load: ScyllaDB had far fewer errors and timeouts during scaling, even at higher traffic levels Why Fast Scaling Matters Most real-world database deployments are overprovisioned to some extent. The extra capacity helps sustain traffic fluctuations and short-lived bursts. It also supports routine maintenance tasks, like applying security patches, rolling out infrastructure maintenance, or recovering from replica failures. Another important consideration in real-world deployments is that benchmark reports often overlook traffic variability over time. In practice, only a subset of workloads consistently demand high baseline throughput, with low variability from their peak needs. Most workloads follow a cyclical pattern, with daily peaks during active hours and significantly lower baseline traffic during off-hours. A diurnal workload example, ranging between 50K to 250K operations per second in a day Fast scaling is also critical for handling unexpected events, such as viral traffic spikes, flash loads, backlog drains after cascading failures, or sudden pressure from upstream systems. It’s especially valuable when traffic has large peak-to-baseline swings, capacity needs to shift often, responses to load must be quick, or costs depend on scaling back down immediately after a surge. Comparing Tablets vs vNodes Fast scaling is ultimately a data distribution problem, and Cassandra’s vNodes and ScyllaDB’s tablets handle that distribution in distinctly different ways. Here’s more detail on the differences we previewed earlier. Apache Cassandra Apache Cassandra follows a token ring architecture. When a node joins the cluster, it is assigned a number of tokens (the default is 16), each representing a portion of the token ring. The node becomes responsible for the data whose partition keys fall within its assigned token ranges. During node bootstrap, existing replicas stream the relevant data to the new replica based on its token ownership. Conversely, when a node is removed, the process is reversed. Cassandra generally recommends avoiding concurrent topology changes; in practice, many operators add/remove nodes serially to reduce risk during range movements. Digression: In reality, topology changes in an Apache Cassandra cluster are plain unsafe. We explained the reasons in a previous blog, and pointed out that even its community acknowledged some of its design flaws. In addition to the administrative overhead involved in scaling a Cassandra cluster, there are other considerations. Adding nodes with higher CPU and memory is not straightforward. It typically requires a new tuning round and manually assigning a higher weight (increasing the number of tokens) to better match capacity. After bootstrap operations, Cassandra requires an intermediary step (cleanup) for older replicas in order to free up disk space and eliminate the risk of data resurrection. Lastly, multiple scaling rounds introduce significant streaming overhead since data is continuously shuffled across the cluster. Cassandra Token Ring ScyllaDB ScyllaDB introduced tablets starting with the 2024.2 release. Tablets are the smallest unit of replication in ScyllaDB and can be migrated independently across the cluster. Each table is dynamically split into tablets based on its size, with each tablet being assigned to a subset of replicas. In effect, tablets are smaller, manageable fragments of a table. As the topology evolves, tablet state transitions are triggered. A global load balancer balances tablets across the cluster, accounting for heterogeneity in node capacity (e.g., assigning more tablets to replicas with greater resources). Under the hood, Raft provides the underlying consensus mechanism that serializes tablet transitions in a way that avoids conflicting topology changes and ensures correctness. The load balancer is hosted on a single node, but not a designated node. If that node crashes or goes down for maintenance, the load balancer will start on another node. Raft and tablets effectively decouple topology changes from streaming operations. Users can orchestrate topology changes in parallel with minimal administrative overhead. ScyllaDB does not require a post-bootstrap cleanup phase. That allows for immediate request serving and more efficient data movement across the network. Visual representation of tablets state transitions Adding Nodes Starting with a 3-node cluster, we ran our “real-life” mixed workload targeting 70% of each database’s inferred total capacity. Before any scaling activity, both ScyllaDB and Cassandra were warmed up to ensure disk and cache activity were in effect. Note: Configuration details are provided in the Appendix. We then started the mixed workload and let it run for another 30 minutes to establish a performance baseline. At this point, we bootstrapped 3 additional nodes, expanding the cluster to 6 nodes. We then allowed the workload to run for an additional 30 minutes to observe the effects of this first scaling step. We increased traffic proportionally. After sustaining it for another 30 minutes, we bootstrapped 3 more nodes, bringing each cluster to a total of 9 nodes. Finally, we increased traffic one last time to ensure each database could sustain its anticipated traffic. Note: See the Appendix for details on the test setup and our Cassandra tuning work. The following table shows the target throughput used during and after each scaling step along with each cluster’s inferred maximum capacity: Nodes ScyllaDB Cassandra 3 (baseline) 196K ops/sec (Max 280K) 56K ops/sec (Max 80K) 6 392K ops/sec (Max 560K) 112K ops/sec (Max 160K) 9 672K ops/sec (Max 840K) 168K ops/sec (Max 240K) We conducted this scaling exercise twice for each database, introducing a minor variation in each run. For ScyllaDB, we bootstrapped all 6 additional nodes in parallel. For Cassandra, we enabled both the Key Cache and Row Cache, as we observed it performed better overall under our initial performance results. Comparison of different scaling approaches At first glance, it might look like ScyllaDB offers only a modest improvement over Cassandra (somewhere between 1.25X and 3.6X faster). But there are deeper nuances to consider. Resiliency In both of our Cassandra benchmarks, we observed a high rate of errors, including frequent timeouts and OverloadedExceptions reported by the server. Notably, our client was configured with an exponential backoff, allowing up to 10 retries per operation. In this environment, both Cassandra configurations showed elevated error rates under sustained load during scaling. The following table summarizes the number of errors observed by the client during the tests: Kind Step Throughput Retries Cassandra 5.0 – Page Cache 3 → 6 nodes 56K ops/sec 2010 Cassandra 5.0 – Page Cache 6 → 9 nodes 112K ops/sec 0 Cassandra 5.0 – Row & Key Cache 3 → 6 nodes 56K ops/sec 5004 Cassandra 5.0 – Row & Key Cache 6 → 9 nodes 112K ops/sec 8779 With the sole exception of scaling from 6 to 9 nodes in the Page Cache scenario, all other Cassandra scaling exercises resulted in noticeable traffic disruption, even while handling 3.5X less traffic than ScyllaDB. In particular, the “Row & Key Cache” configuration proved itself unable to sustain prolonged traffic, ultimately forcing us to terminate that test prematurely. Performance The earlier comparison chart also highlights the cost of repeated streaming across incremental expansion steps. Although bootstrap duration is governed by the volume of data being streamed and decreases as more nodes are added, each scaling operation redundantly re-streams data that was already redistributed in prior steps. This introduces significant overhead, compounding both the time and performance of scaling operations. As demonstrated, scaling directly from 3 to 9 nodes using ScyllaDB tablets eliminates the intermediary incremental redistribution overhead. By avoiding redundant streaming at each intermediate step, the system performs a single, targeted redistribution of tablets, resulting in a significantly faster and more efficient bootstrap process. ScyllaDB tablet streaming from 3 to 9 nodes After the scale out operations completed, we ran the following load tests to assess each database’s ability to withstand increased traffic: For ScyllaDB, we increased traffic to 80% of its peak capacity (280 * 3 * 0.8 = 672 Kops) For Cassandra, we increased traffic to 100% (240 Kops) and 125% (300 Kops) of its peak capacity to validate our starting assumptions ScyllaDB sustains 672 Kops/sec with load (per vCPU) around 80% utilization, as expected. Apache Cassandra latency variability under different throughput rates (240K vs 300K ops/sec) Cassandra maintained its expected 240K peak traffic. However, it failed to sustain 300K over time – leading to increased pauses and errors. This outcome was anticipated since the test was designed to validate our initial baseline assumptions, not to achieve or demonstrate superlinear scaling. Expectations In our tests, ScyllaDB scaled faster and delivered greater improvements in latency and throughput at each step. That reduces the number of scaling operations required. The compounded benefits translate to significantly faster capacity expansion. In contrast, Cassandra’s scaling behavior is more incremental. The initial scale-out from 3 to 6 nodes took 24 minutes. The subsequent step from 6 to 9 nodes introduced additional overhead, requiring 16 minutes. From this observation, we empirically derived a formula to model the scaling factor per step: 16 = 24 × (0.5/1.0)^overhead Solving for the exponent, we approximated the streaming overhead factor as 0.6. Using this, we constructed a practical formula to estimate Cassandra’s bootstrap duration at each scale step: Bootstrap_time ≈ Base_time × (data_to_stream / data_per_node)^0.6 With these formulas, we can project the bootstrap times for subsequent scaling steps. Based on our earlier performance results (where Cassandra sustained approximately 80K ops/sec for every 3-node increase), 27 total nodes of Cassandra would be required to match the throughput achieved by ScyllaDB. The following table presents the estimated cumulative bootstrap times needed for Cassandra to reach ScyllaDB performance, using the previously derived formula and applying the 0.6 streaming overhead factor at each step: Nodes Data to Stream Bootstrap Time Cumulative Time Peak Capacity 3 2.0TB – 0 min 80K 3 → 6 1.0TB 24.0 min 24.0 min 160K 6 → 9 0.67TB 15.8 min 39.8 min 240K 9 → 12 0.50TB 12.4 min 52.2 min 320K 12 → 15 0.40TB 10.4 min 62.6 min 400K 15 → 18 0.33TB 9.0 min 71.6 min 480K 18 → 21 0.29TB 8.1 min 79.7 min 560K 21 → 24 0.25TB 7.3 min 87.0 min 640K 24 → 27 0.22TB 6.7 min 93.7 min 720K Time to reach throughput capacity for bootstrap operations As the table and chart visually show, ScyllaDB responds to capacity needs 7.2X faster than Cassandra. That’s before accounting for the added operational and maintenance overhead associated with the process. Cleanup Cleanup is a process to reclaim disk space after a scale-out operation takes place in Cassandra. As the Cassandra documentation states: As a safety measure, Cassandra does not automatically remove data from nodes that “lose” part of their token range due to a range movement operation (bootstrap, move, replace). (…) If you do not do this, the old data will still be counted against the load on that node. We estimated the following cleanup times after scaling to 9 nodes with unthrottled compactions: Unlike topology changes, Cassandra cleanup operations can be executed in parallel across multiple replicas, rather than being serialized. The trade-off, however, is a temporary increase in compaction activity – something that may impact system performance through its execution. In practice, many users choose to run cleanup serially or per rack to minimize disruption to user-facing traffic. Despite its parallelizability, careful coordination is often preferred in production environments to minimize latency impact. The following table outlines the total time required under various cleanup strategies: In conclusion, ScyllaDB scaled faster and sustained higher throughput during scale-out, and it removes cleanup as part of the scaling cycle. Even for users willing to accept the risk of running cleanup in parallel across all Cassandra nodes, ScyllaDB still offers 9X faster capacity response time, once the minimum required cleanup time is factored into Cassandra’s previously estimated bootstrap durations. These results reflect how both databases behave under one specific scaling pattern. Teams should benchmark against their own workload shapes and operational constraints to see how these architectural differences play out in their particular environment. Parting Thoughts We know readers are (rightfully) skeptical of vendor benchmarks. As discussed earlier, Cassandra and ScyllaDB rely on fundamentally different scaling models, which makes designing a perfect comparison inherently difficult. The scaling exercises demonstrated here were not designed to fully maximize ScyllaDB tablets’ potential. The test design actually favors Cassandra by focusing on symmetrical scaling. Asymmetrical scaling scenarios would better highlight the advantage of tablets vs vNodes. Even with a design that favored Cassandra’s vNodes model, the results show the impact of tablets. ScyllaDB sustained 4X the throughput of Apache Cassandra while maintaining consistently lower P99 latencies under similar infrastructure. Interpreted differently, ScyllaDB delivers comparable performance to Cassandra using significantly smaller instances, which could then be scaled further by introducing larger, asymmetric nodes as needed. This approach (scaling from 3 small nodes to another 3 [much larger] nodes) optimizes infrastructure TCO and aligns naturally with ScyllaDB Tablets architecture. However, this would be far more difficult to achieve (and test) in Cassandra in practice. Also, the tests intentionally did not use large instances to avoid favoring ScyllaDB. ScyllaDB’s shard-per-core architecture is designed to linearly scale across large instances without requiring extensive tuning cycles, which are often encountered with Apache Cassandra. For example, a 3-node cluster running on the largest AWS Graviton4 instances can sustain over 4M operations per second. When combined with Tablets, ScyllaDB deployments can scale from tens of thousands to millions of operations per second within minutes. Finally, remember that performance should be just one component in a team’s database evaluation. ScyllaDB offers numerous features beyond Cassandra (local and global indexes, materialized views, workload prioritization, per query timeouts, internal cache, and advanced dictionary-based compression, for example). Appendix: How We Ran the Tests Both ScyllaDB and Cassandra tests were carried out in AWS EC2 in an apples-to-apples scenario. We ran our tests on a 3-node cluster running on top of i4i.4xlarge instances placed under the same Cluster Placement Group to further reduce networking round-trips. Consequently, each node was placed on an artificial rack using the GossipingPropertyFileSnitch. As usual, all tests used LOCAL_QUORUM as the consistency level, a replication factor of 3. They used NetworkTopologyStrategy as the replication strategy. To assess scalability under real-world traffic patterns, like Gaussian and other similar bell curve shapes, we measured the time required to bootstrap new replicas to a live cluster without disrupting active traffic. Based on these results, we derived a mathematical model to quantify and compare the scalability gaps between both systems. Methodology To assess scalability under realistic conditions, we ran performance tests to simulate typical production traffic fluctuations. The actual benchmarking is a series of invocations of ScyllaDB’s fork of latte with a consistency level of LOCAL_QUORUM. To test scalability, we used a “real-life” mixed distribution, with the majority (80%) of operations distributed over a hot set, and the remaining 20% iterating over a cold set. latte is the Lightweight Benchmarking Tool for Apache Cassandra as developed by Piotr Kołaczkowski, a DataStax Software Engineer. Under the hood, latte relies on ScyllaDB’s Rust driver, compatible with Apache Cassandra. It outperforms other widely used benchmarking tools, provides better scalability and has no GC pauses, resulting in less latency variability on the results. Unlike other benchmarking tools, latte (thanks to its use of Rune) also provides a flexible syntax for defining workloads closely tied on how developers actually interact with their databases. Lastly, we can always brag we did it in Rust, just because… 🙂 We set baseline traffic at 70% of its observed peak before P99 latency crossed a 10ms threshold. This was to ensure both databases retained sufficient CPU and I/O headroom to handle sudden traffic and concurrency spikes, as well as the overhead of scaling operations. Setup The following table shows the infrastructure we used for our tests: Cassandra/ScyllaDB Loaders EC2 Instance type i4i.4xlarge c6in.8xlarge Cluster size 3 1 vCPUs (total) 16 (48) 32 RAM (total) 128 (384) GiB 64 GiB Storage (total) 1 x 3.750 AWS Nitro SSD EBS-only Network Up to 25 Gbps 50 Gbps ScyllaDB and Cassandra nodes, as well as their respective loaders, were placed under their own exclusive AWS Cluster Placement Group for low-latency networking. Given the side-effect of all replicas being placed under the same availability zone, we placed each node under an artificial rack using the GossipingPropertyFileSnitch. The schema used through all testing suites resembles the same schema as the default cassandra-stress, whereas the keyspace relies on NetworkTopologyStrategy with a replication factor of 3: CREATE TABLE IF NOT EXISTS keyspace1.standard1 ( key blob PRIMARY KEY, c0 blob, c1 blob, c2 blob, c3 blob, c4 blob ) ; We used a payload of 1010 bytes, where: 10-bytes represent the keysize, and; Each of the 5 columns is a distinct 200-byte blob Both databases were pre-populated with 2 billion partitions for an approximate (replicated) storage utilization of ~2.02TB. That’s about 60% disk utilization, considering the metadata overhead. Tuning Apache Cassandra Cassandra was originally designed to be run on commodity hardware. As such, one of its features is shipping with numerous different tuning options suitable for various use cases. However, this flexibility comes with a cost: tuning Cassandra is entirely up to its administrators, with limited guidance from online resources. Unlike ScyllaDB, an Apache Cassandra deployment requires users to manually tune kernel settings, set user limits, configure the JVM, set disks’ read-ahead, decide upon compaction strategies, and figure out the best approach for pushing metrics to external monitoring systems. To make things worse, some configuration file comments are outdated or ambiguous across versions. For example, CASSANDRA-16315 and CASSANDRA-7139 describe problems involving the default setting for concurrent compactors and offer advice on how to tune that parameter. Along those lines, it’s worth mentioning Amy Tobey’s Cassandra tuning guide (perhaps the most relevant Cassandra tuning resource available to date), where it says: “The inaccuracy of some comments in Cassandra configs is an old tradition, dating back to 2010 or 2011. (…) What you need to know is that a lot of the advice in the config commentary is misleading. Whenever it says “number of cores” or “number of disks” is a good time to be suspicious. (…)” – Excerpt from Amy’s Cassandra tuning guide, cassandra.yaml section Tuning the JVM is a journey of its own. Cassandra 5.0 production recommendations don’t mention it, and the jvm-* files page only deals with the file-based structure as shipped with the database. Although DataStax’s Tuning Java resources does a better job on providing recommendations, it warns to adjust “settings gradually and test each incremental change.” Further, we didn’t find any references to ZGC (available as of JDK17) on either the Apache Cassandra or DataStax websites. That made us wonder whether this garbage collector was even recommended. Eventually, we settled on using settings similar to those that TheLastPickle used in their Apache Cassandra 4.0 Benchmarks. During our scaling tests, we hit another inconsistency: we noticed Cassandra’s streaming operations had a default cap of 24MiB/s per node, resulting in suboptimal transfer times. Upon raising those thresholds, we noticed that: Cassandra 4.0 docs mentioned tuning the stream_throughput_outbound_megabits_per_sec option Both Cassandra 4.1 and Cassandra 5.0 docs referenced the stream_throughput_outbound option This Instaclustr article (or carefully interpreting cassandra_latest.yaml) seem like the best resource for understanding the correct entire_sstable_stream_throughput_outbound option. In other words, 3 distinct settings exist for tuning the previous 3 major releases of Cassandra. If your organization is looking to upgrade, we strongly encourage you to conduct a careful review and full round of testing on your own. This is not an edge case; others noted similar upgrade problems under the Apache Cassandra Mailing List. CASSANDRA-20692 demonstrates that Apache Cassandra 5 failed to notice a potential WAL corruption under its newer Direct IO implementation, as issuing I/O requests without O_DSYNC could manifest as data loss during abrupt restarts. This, in turn, gives users a false sense of improved write performance. Configuring Apache Cassandra is not intuitive. We used cassandra_latest.yaml as a starting point, and ran multiple iterations of the same workload under a variety of settings and different GC settings. The results are shown below and demonstrate how little tuning can have a dramatic impact on Cassandra’s performance (for better or for worse). We started by evaluating the performance of G1GC and observed that tail latencies were severely affected beyond a throughput of 40K/s. Simply switching to ZGC gave a nice performance boost, so we decided to stick with it for the remainder of our testing. The following table shows the performance variability of Cassandra 5.0 while using different tuning settings (it’s ordered from best to worst case): Test Kind Garbage Collector Read-ahead Compaction Throughput P99 Latency Throughput Cassandra RA4 Compaction256 ZGC 4KB 256MB/s 6.662ms 120K/s Cassandra RA4 Compaction0 ZGC 4KB Unthrottled 8.159ms 120K/s Cassandra RA8 Compaction256 ZGC 8KB 256MB/s 4.657ms 100K/s Cassandra RA8 Compaction0 ZGC 8KB Unthrottled 4.903ms 100K/s Cassandra G1GC G1GC 4KB 256MB/s 5.521ms 40K/s Although we spent a considerable amount of time tuning Cassandra to provide an unbiased and neutral comparison, we eventually found ourselves in a feedback loop. That is, the reported performance levels are only applicable for the workload being stressed running under the infrastructure in question. If we were to switch to different instance types or run different workload profiles, then additional tuning cycles would be necessary. We anticipate that the majority of Cassandra deployments do not undergo the level of testing we carried out on a per-workload basis. We hope that our experience may prevent other users from running into the same mistakes and gotchas that we did. We’re not claiming that our settings are the absolute best, but we don’t expect that further iterations will yield large performance improvements beyond what we observed. Tuning ScyllaDB We carried out very little tuning for ScyllaDB beyond what is described in the Configure ScyllaDB documentation. Unlike Apache Cassandra, thescylla_setup script takes care of most of the

nitty-gritty details related to optimal OS tuning. ScyllaDB also

used tablets for data distribution. We targeted a minimum of 100

tablets/shard with the following CREATE KEYSPACE

statement: CREATE KEYSPACE IF NOT EXISTS keyspace1 WITH

REPLICATION = { 'class': 'NetworkTopologyStrategy', 'datacenter1':

3 } AND tablets = {'enabled': true, 'initial': 2048};

Limitations of our Testing Performance testing often fails to

capture real-world performance metrics tied to the semantics and

access patterns of applications. Aspects such as variable

concurrency, the impact of DELETEs (tombstones), hotspots,

and large partitions were beyond the scope of our testing. Our work

also did not aim to provide a feature-specific comparison. While

Apache Cassandra 5.0 ships with newer (and less battle-tested)

features like

Storage-attached Indexes (SAI), ScyllaDB also ships with

Workload Prioritization,

Local Secondary Indexes, and

Synchronous Materialized Views, all with no equivalent

counterpart. However, we ensured both databases’ transparent and

newer features were used, such as Cassandra’s Trie Memtables,

Trie-indexed SSTables and its newer Unified Compaction Strategy, as

well as ScyllaDB’s features like Tablets,

Shard-awareness, SSTable Index Caching, and so forth. Future

tests will use ScyllaDB’s Trie-indexed SSTables. Also note that

both databases now offer Vector Search, which was not in scope for

this project. Finally, this benchmark focuses specifically on

scaling operations, not steady-state performance. ScyllaDB has

historically demonstrated higher throughput and lower latency than

Cassandra in multiple performance benchmarks. Cassandra 5

introduces architectural improvements, but our preliminary testing

shows that ScyllaDB maintains its performance advantage. Producing

a full apples-to-apples benchmark suite for Cassandra 5 is a

sizable project that’s outside the scope of this study. For teams

evaluating a migration, the best insights will come from testing

your real-life workload profile, data models, and SLAs directly on

ScyllaDB. If you are running your own evaluations (tip: ScyllaDB

Cloud is the easiest way), our technical

team can review your setup and share tips for accurately

measuring ScyllaDB’s performance in your specific environment. Announcing ScyllaDB 2025.4, with Extended Tablets Support, DynamoDB Alternator Updates & Trie-Based Indexes

An overview of recent ScyllaDB changes, including extended tablets support, native vector search, Alternator enhancements, a new SSTable index format, and new instance support The ScyllaDB team is pleased to announce the release of ScyllaDB 2025.4, a production-ready ScyllaDB Short Term Support (STS) Minor Feature Release. More information on ScyllaDB’s Long Term Support (LTS) policy is available here. Highlights of the 2025.4 release include: Tablets now support Materialized Views (MV), Secondary Indexes (SI), Change Data Capture (CDC), and Lightweight Transactions (LWT). This fully bridges the previous feature gap between Tablets and vNodes. ScyllaDB Vector Search is now available (in GA), introducing native low-latency Approximate Nearest Neighbor (ANN) similarity search through CQL. See the Getting Started Guide and try it out. Alternator (ScyllaDB’s DynamoDB-compatible API) fully supports Tablets by following tablets_mode_for_new_keyspaces configuration flag, except for the still-experimental Streams. The new Trie-based index format improves indexing efficiency. New deployment options with i8g and i8ge show significant performance advantages over i4i, i3en as well as i7i and i7ie. For full details on how to use these features — as well as additional changes — see the release notes. Read Release Notes Vector Search Vector Search Support ScyllaDB 2025.4 introduces native Vector Search to power AI-driven applications. By integrating vector indexing directly into the ScyllaDB ecosystem, teams can now perform similarity searches without moving data to a separate vector database. CQL Integration: Store and query embeddings using standard CQL syntax. ANN Queries: Support for Approximate Nearest Neighbor (ANN) search for RAG and personalization. Dedicated Service: Managed vector indexing service ensures high performance without impacting core database operations. Availability: Initially launched on ScyllaDB Cloud. For more information: ScyllaDB Vector Search: 1B Vectors with 2ms P99s and 250K QPS Throughput Building a Low-Latency Vector Search Engine for ScyllaDB Quick Start Guide to Vector Search Extended Tablets Support The new release extends ScyllaDB’s tablet-based elasticity to use cases that involve advanced ScyllaDB capabilities such as Change Data Capture, Materialized Views, and Secondary Indexes. It also extends tablets to ScyllaDB’s DynamoDB-compatible API (Alternator). Alternator Improvements Alternator, ScyllaDB’s DynamoDB-compatible API, now more closely matches DynamoDB’s GetRecords behavior. Event metadata is fully populated, including EventSource=aws:dynamodb, awsRegion set to the receiving node’s datacenter, an updated eventVersion, and the sizeBytes subfield in DynamoDB. Performance was improved by caching parsed expressions in requests. That caching reduces overhead for complex expressions and provides ~7–15% higher single-node throughput in tested workloads. Alternator also adds support for per-table metrics (for additional insight into Alternator usage). Trie-Based SSTable Index Format A new trie-based SSTable index format is designed to improve lookup performance and reduce memory overhead. The default SSTable format remains “me,” but a new “ms” format is available, which uses trie-based indexes. The new format is disabled by default and can be enabled by settingsstable_format: ms in

scylla.yaml. When enabled, only newly created SSTables

use the trie-based index; existing SSTables keep their current

format until rewritten with nodetool upgradesstables. New

Deployment Options This release expands support to all I7i and I7ie

instance types (beyond the previously supported i7i.large,

i7i.xlarge, i7i.2xlarge). These instances offer improved

price-to-performance compared to previous-generation instances.

Support was also added for the i8g and i8ge

families, which provide better price-to-performance than

x86-based instances. Read

the Release Notes for More Details The Taming of Collection Scans

Explore several collection layouts for efficient scanning, including a split-list structure that avoids extra memory Here’s a puzzle that I came across when trying to make tasks wake up in Seastar be a no-exception-throwing operation (related issue): come up with a collection of objects optimized for “scanning” usage. That is, when iterating over all elements of the collection, maximize the hardware utilization to process a single element as fast as possible. And, as always, we’re expected to minimize the amount of memory needed to maintain it. This seemingly simple puzzle will demonstrate some hidden effects of a CPU’s data processing. Looking ahead, such a collection can be used, for example, as a queue of running tasks. New tasks are added at the back of the queue; when processed, the queue is scanned in front-to-back order, and all tasks are usually processed. Throughout this article, we’ll refer to this use case of a collection being the queue of tasks to execute. There will be occasional side notes using this scenario to demonstrate various concerns. We will explore different ways to solve this puzzle of organizing collections for efficient scanning. First, we compare three collections: array, intrusive list, and array of pointers. You will see that the scanning performance of those collections differs greatly, and heavily depends on the way adjacent elements are referenced by the collection. After analyzing the way the processor executes the scanning code instructions, we suggest a new collection called a “split list.” Although this new collection seems awkward and bulky, it ultimately provides excellent scanning performance and memory efficiency. Classical solutions First consider two collections that usually come to mind: a plain sequential array of elements and a linked list of elements. The latter collection is sometimes unavoidable, particularly when the elements need to be created and destroyed independently and cannot be freely moved across memory. As a test, we’ll use elements that contain random, pre-populated integers and a loop that walks all elements in the collection and calculates the sum of those integers. Every programmer knows that in this case, an array of integers will win because of cache efficiency. To exclude the obvious advantage of one collection over another, we’ll penalize the array and prioritize the list. First, each element will occupy a 64-byte slot even when placed in an array, so walking a plain array doesn’t benefit from caching several adjacent elements. Second, we will use an intrusive list, which means that the “next” pointer will be stored next to the element value itself. The processor can then read both the pointer and the value with a single fetch from memory to cache. The expectation here is that both collections will behave the same. However, a scanning test shows that’s not true, especially on a large scale. The plot above shows the time to process a single entry (vertical axis) versus the number of elements in the list (horizontal axis). Both axes use a logarithmic scale because the collection size was increased ten times at each new test step. Plus, the vertical axis just looks better this way. So now we have two collections – an array and a list – and the list’s performance is worse than the array’s. However, as mentioned above, the list has an undeniable advantage: elements in the list are independent of each other (in the sense that they can be allocated and destroyed independently). A less obvious advantage is that the data type stored in a list collection can be an abstract class, while the actual elements stored in the list can be specific classes that inherit from that base class. The ability to collect objects of different types can be crucial in the task processing scenario described above, where a task is described as an abstract base class and specific task implementations inherit from it and implement their own execution methods. Is it possible to build a collection that can maintain its elements independently, as a list of elements does, yet still provide scanning performance that’s the same (or close to) that of the array? Not so classical solution Let’s make an array of elements be “dispersed,” like a list, in a straightforward manner by turning each array element into a pointer to that element, and allocating the element itself elsewhere, as if it were prepared to be inserted into a list. In this array, pointers will no longer be aligned to a cache-line, thus letting the processor benefit from reading several pointers from memory at once. Elements are still 64-bytes in size, to be consistent with previous tests. The memory for pointers is allocated contiguously, with a single large allocation. This is not ideal for dynamic collection, where the number of elements is not known beforehand: the larger the collection grows, the more re-allocations are needed. It’s possible to overcome this by maintaining a list of sub-arrays. Looking ahead, just note that this chunked array of pointers will indeed behave slightly worse than a contiguous one. All further measurements and analysis refer to the contiguous collection. This approach actually looks worse than the linked list because it occupies more memory than the list. Also, when walking the list, the code touches one cache line per element – but when walking this collection, it additionally populates the cache with the contents of that array of pointers. Running the same scanning test shows that this cost is imaginary and the collection beats the list several times, approaching the plain array in its per-element efficiency. The processor’s inner parallelism To get an idea of why an array of pointers works better than the intrusive list, let’s drill down to the assembly level and analyze how the instructions are executed by the processor. Here’s what the array scanning main loop looks like in assembly:x: mov (%rdi,%rax,8),%rax mov 0x10(%rax),%eax

add %rax,%rcx lea 0x1(%rdx),%eax mov %rax,%rdx cmp %rsi,%rax jb

x We can see two memory accesses – the first moves the

pointer to the array element to the ‘rax’ register,

and the second fetches the value from the element into its

‘eax’ 32-bit sub-part. Then there comes in-register

math and conditional jumping back to the start of the loop to

process the next element. The main loop of the list scanning code

looks much shorter: x: mov 0x10(%rdi),%edx mov (%rdi),%rdi

add %rdx,%rax test %rdi,%rdi jne x Again, there are two

memory accesses – the first fetches the value pointer into the

‘edx’ register and the next one fetches the pointer to

the next element to the ‘rdi’ register. Instructions

that involve fetching data from memory can be split into four

stages: i-fetch – The processor fetches the instruction itself from

memory. In our case, the instruction is likely in the instruction

cache, so the fetch goes very fast. decode – The processor decides

what the instruction should do and what operands are needed for

this. m-fetch – The processor reads the data it needs from memory.

In our case, elements are always read from memory because they are

“large enough” not to be fetched into cache with anything else,

while array pointers are likely to sit in cache. exec – The

processor executes the instruction. Let’s illustrate this sequence

with a color bar:

Also, we know that modern processors can run multiple

instructions in parallel, by executing parts of different

instructions at the same time in different parts of the conveyor,

as well as running instructions fully in parallel. One

example of this parallel execution can be seen in the

array-scanning example above, namely the add %rax,%rcx

lea 0x1(%rdx),%eax part. Here, the second instruction is

the increment of the index that’s used to scan through the array of

pointers. The compiler rendered this as lea

instruction instead of the inc (or add)

one because inc and lea are executed in

different parts of the pipeline. When placed back-to-back,

they will truly run in parallel. If the inc was used,

the second instruction would have to spend some time in the same

pipeline stage as the add. Here’s what executing

the above array scan can look like:

Here, fetching the element pointer from the array is short because

it likely happens from cache. Fetching the element’s value is long

(and painted darker) because the element is most certainly not in

cache (and thus requires a memory read). Also, fetching the value

from the element happens after the element pointer is fetched into

the register. Similarly, the instruction that adds value to the

result cannot execute before the value itself is fetched from

memory, so it waits after being decoded. And here’s what scanning

the list can look like:

At first glance, almost nothing changed. The difference is that the

next pointer is fetched from memory and takes a long time, but the

value is fetched from cache (and is faster). Also, fetching the

value can start before the next pointer is saved into the register.

Considering that during an array scan, the “read element pointer

from array” is long at times (e.g., when it needs to read the next

cache line from memory), it’s still not clear why list scanning

doesn’t win at all. In order to see why the array of pointers wins,

we need to combine two consecutive loop iterations. First comes the

array scan:

It’s not obvious, but two loop iterations can run like that.

Fetching the pointer for the next element is pretty much

independent from fetching the pointer of the previous element; it’s

just the next element of an array that’s already in the cache. Just

like predicting the next branches, processors can “predict” that

the next memory fetch will come from the pointer sitting next to

the one being processed and start loading it ahead of time. List

scanning cannot afford that parallelism even if the processor

“foresees” that the fetched pointer will be dereferenced. As a

consequence, its two loop iterations end up being serialized:

Note that the processor can only start fetching the next element

after it finishes fetching the next pointer itself, so the

parallelism of accessing elements is greatly penalized here. Also

note that despite how it seems in the above images, scanning the

list can be many times slower than scanning the array,

because blue bars (memory fetches) are in reality many times longer

than the others (e.g., those fetching the instruction, decoding it,

and storing the result in the register). A compromise solution The

array of pointers turned out to be a much better solution than the

list of elements, but it still has an inefficiency: extra memory

that can grow large. Here we can say that this algorithm has O(N)

memory complexity, meaning that it requires extra memory that’s

proportional to the number of elements in the collection.

Allocating it can be troublesome for many reasons – for example,

because of memory fragmentation and because, at large scale,

growing the array would require copying all the pointers from one

place to another. There are ways to mitigate the problem of

maintaining this extra memory, but is it possible to eliminate it

completely? Or at least make it “constant complexity” (i.e.,

independent from the number of elements in it)? The requirement

to not allocate extra memory can be crucial in task processing

scenarios. In it, the auxiliary memory is allocated when an element

is appended to the existing collection. And a new task is appended

to the run-queue when it’s being woken up. If the allocation fails,

the appending also fails as well as the wake-up call. And having

non-failing wake-ups can be critical. It looks like letting

the processor fetch independent data in different

consecutive loop iterations is beneficial. With a list, it would be

good if adjacent elements were accessed independently. That can be

achieved by splitting the list into several sub-lists, and – when

iterating the whole collection – processing it in a round-robin

manner. Specifically, take an element from the first list, then

from the second, … then from the Nth, then advancing on the first,

then advancing on the second, and so on.

The scanning code is made with the assumption that the collection

only grows by appending elements to one of its ends – the front or

the back end. This perfectly suits the task-processing usage

scenario and allows making the scanning code break condition to be

very simple: once a null element is met in either of the lists, all

lists after it are empty as well, so scanning can stop.

Below is the simplistic implementation of the scanning loop. A full

implementation that handles appends is a bit more hairy and is

based on the C++ “iterator” concept. But overall, it has the same

efficiency and resulting assembly code. First, checking this list

with N=2

OK, scanning two lists “in parallel” definitely helps. Since the

number of splits is compile-time constant, we now need to run

several tests to see which value is the most efficient one.

The more we split the list, the worse it seems to behave at

small scales, but the better at large scale. Splits at 16 and 32

lanes seem to “saturate” the processor’s parallelism ability.

Here’s how the results look at a different angle:

Here, the horizontal axis shows N (the number of lists

in the collection), and individual lines on the plot correspond to

different collection sizes starting from 10 elements and ending at

one million. And both axes are at logarithmic scale too. At a low

scale with 10 and 100 elements, adding more lists doesn’t improve

the scanning speed. But at larger scales, 16 parallel lists are

indeed the saturation point. Interestingly, the assembly code of

the split-list main loop part contains two times more instructions

than the plain list scan. x: mov %eax,%edx add $0x1,%eax and

$0xf,%edx mov -0x78(%rsp,%rdx,8),%rcx mov 0x10(%rcx),%edi mov

0x8(%rcx),%rcx add %rdi,%rsi mov %rcx,-0x78(%rsp,%rdx,8) cmp

%r8d,%eax jne x It also has two times more memory access

than the plain list scanning code. Nonetheless, since the memory is

better organized, prefetching it in a parallel manner makes this

code win in terms of timing. Comparing different processors (and

compilers) The above measurements were done on an

AMD Threadripper processor and the binary was compiled with a

GCC-15

compiler. It’s interesting to check what code different

compilers render and, more importantly, how different processors

behave. First, let’s look at it with the instructions set. No big

surprises here; plain list is the shortest code, split list is the

longest:

Running the tests on different processors, however, renders very

different results. Below are the number of cycles a processor needs

to process a single element. Since the plain list is the outlier,

it will be shown on its own plot. Here are the top performers –

array, array of pointers, and split list:

The split list is, as we’ve seen, the slowest one. But it’s not

drastically different. More interesting is the way the Xeon

processor beats the other competitors. A similar ratio was measured

for plain list processing by different processors:

But, again, even on the Xeon processor, it’s an order of magnitude

slower than the split list. Summing things up In this article, we

explored ways to organize a collection of objects to allow for

efficient scanning. We compared four collections – array, intrusive

list, array of pointers, and split-list. Since plain arrays have

problems maintaining objects independently, we used them as a base

reference and mainly compared three other collections with each

other to find out which one behaved the best. From the experiments,

we discovered that an array of pointers provided the best timing

for single-element access, but required a lot of extra memory. This

cost can be mitigated to some extent, but the memory itself doesn’t

go away. The split-list approach showed comparable (almost as good)

performance. And the advantage of the split-list solution is that

it doesn’t require extra memory to work.

Top Blogs of 2025: Rust, Elasticity, and Real-Time DB Workloads

Let’s look back at the top 10 ScyllaDB blog posts published in 2025, as well as 10 “classics” that are still resonating with readers. But first: thank you to all the community members who contributed to our blogs in various ways…from users sharing best practices at Monster SCALE Summit and P99 CONF, to engineers explaining how they raised the bar for database performance, to anyone who has initiated or contributed to the discussion on HackerNews, Reddit, and the like. And if you have suggestions for additional blog topics, please share them with us on our socials. With no further ado, here are the most-read blog posts that we published in 2025… Inside ScyllaDB Rust Driver 1.0: A Fully Async Shard-Aware CQL Driver Using Tokio By Wojciech Przytuła The engineering challenges and design decisions that led to the 1.0 release of ScyllaDB Rust Driver. Read: Inside ScyllaDB Rust Driver 1.0: A Fully Async Shard-Aware CQL Driver Using Tokio Related: P99 CONF on-demand Introducing ScyllaDB X Cloud: A (Mostly) Technical Overview By Tzach Livyatan ScyllaDB X Cloud just landed! It’s a truly elastic database that supports variable/unpredictable workloads with consistent low latency, plus low costs. Read: Introducing ScyllaDB X Cloud: A (Mostly) Technical Overview Related: ScyllaDB X Cloud: An Inside Look with Avi Kivity Inside Tripadvisor’s Real-Time Personalization with ScyllaDB + AWS By Dean Poulin See the engineering behind real-time personalization at Tripadvisor’s massive (and rapidly growing) scale Read: Inside Tripadvisor’s Real-Time Personalization with ScyllaDB + AWS Related: How ShareChat Scaled their ML Feature Store 1000X without Scaling the Database Why We Changed Our Data Streaming Approach By Asias He How moving from mutation-based streaming to file-based streaming resulted in 25X faster streaming time. Read: Why We Changed Our Data Streaming Approach Related: More engineering blog posts How Supercell Handles Real-Time Persisted Events with ScyllaDB By Cynthia Dunlop How a team of just two engineers tackled real-time persisted events for hundreds of millions of players Read: How Supercell Handles Real-Time Persisted Events with ScyllaDB Related: Rust Rewrite, Postgres Exit: Blitz Revamps Its “League of Legends” Backend Why Teams Are Ditching DynamoDB By Guilherme da Silva Nogueira, Felipe Cardeneti Mendes Teams sometimes need lower latency, lower costs (especially as they scale) or the ability to run their applications somewhere other than AWS Read: Why Teams Are Ditching DynamoDB Related: ScyllaDB vs DynamoDB: 5-Minute Demo A New Way to Estimate DynamoDB Costs By Tim Koopmans We built a new DynamoDB cost analyzer that helps developers understand what their workloads will really cost Read: A New Way to Estimate DynamoDB Costs Related: Understanding The True Cost of DynamoDB Efficient Full Table Scans with ScyllaDB Tablets By Felipe Cardeneti Mendes How “tablets” data distribution optimizes the perfromance of full table scans on ScyllaDB. Read: Efficient Full Table Scans with ScyllaDB Tablets Related: Fast and Deterministic Full Table Scans at Scale How We Simulate Real-World Production Workloads with “latte” By Valerii Ponomarov Learn why and how we adopted latte, a Rust-based lightweight benchmarking tool, for ScyllaDB’s specialized testing needs. Read: How We Simulate Real-World Production Workloads with “latte” Related: Database Benchmarking for Performance Masterclass How JioCinema Uses ScyllaDB Bloom Filters for Personalization By Cynthia Dunlop JioCinema (now Disney+ Hotstar) was operating at a scale that required creative solutions beyond typical Redis Bloom filters. This post explains why and how they used ScyllaDB’s built-in Bloom filters for real-time watch status checks. Read: How JioCinema Uses ScyllaDB Bloom Filters for Personalization Related: More user perspectives Bonus: Top NoSQL Database Blogs From Years Past Many of the blogs published in previous years continued to resonate with the community. Here’s a rundown of 10 enduring favorites: How io_uring and eBPF Will Revolutionize Programming in Linux (Glauber Costa): How io_uring and eBPF will change the way programmers develop asynchronous interfaces and execute arbitrary code, such as tracepoints, more securely. [2020] Database Internals: Working with IO (Pavel Emelyanov): Explore the tradeoffs of different Linux I/O methods and learn how databases can take advantage of a modern SSD’s unique characteristics. [2024] On Coordinated Omission (Ivan Prisyazhynyy): Your benchmark may be lying to you. Learn why coordinated omissions are a concern and how they are handled in ScyllaDB benchmarking. [2021] ScyllaDB vs MongoDB vs PostgreSQL: Tractian’s Benchmarking & Migration (João Pedro Voltani): TRACTIAN compares ScyllaDB, MongoDB, and PostgreSQL and walks through their MongoDB-to-ScyllaDB migration, including challenges and results. [2023] Introducing “Database Performance at Scale”: A Free, Open Source Book (Dor Laor): A practical guide to understanding the tradeoffs and pitfalls of optimizing data-intensive applications for high throughput and low latency. [2023] ScyllaDB vs. DynamoDB Benchmark: Comparing Price Performance Across Workloads (Eliran Sinvani): A comparison of cost and latency across DynamoDB pricing models and ScyllaDB under varied workloads and read/write ratios. [2023] Benchmarking MongoDB vs ScyllaDB: Performance, Scalability & Cost (Dr. Daniel Seybold): A third-party benchmark comparing MongoDB and ScyllaDB on throughput, latency, scalability, and price-performance. [2023] Apache Cassandra 4.0 vs. ScyllaDB 4.4: Comparing Performance (Juliusz Stasiewicz, Piotr Grabowski, Karol Baryla): Benchmarks showing 2×–5× higher throughput and significantly better latency with ScyllaDB versus Cassandra. [2022] DynamoDB: When to Move Out (Felipe Cardeneti Mendes): Why teams leave DynamoDB, including throttling, latency, item size limits, flexibility constraints, and cost. [2023] Rust vs. Zig in Reality: A (Somewhat) Friendly Debate(Cynthia Dunlop): A recap of a P99 CONF debate on systems programming languages with participants from Bun.js, Turso, and ScyllaDB. [2024]Lessons Learned Leading High-Stakes Data Migrations

“No one ever said ‘meh, it’s just our database'” Every data migration is high stakes to the person leading it. Whether you’re upgrading an internal app’s database or moving 362 PB of Twitter’s data from bare metal to GCP, a lot can go awry — and you don’t want to be blamed for downtime or data loss. But a migration done right will not only optimize your project’s infrastructure. It will also leave you with a deeper understanding of your system and maybe even yield some fun “war stories” to share with your peers. To cheat a bit, why not learn from others’ experiences first? Enter Miles Ward (CTO at SADA and former Google and AWS cloud lead) and Tim Koopmans (Senior Director at ScyllaDB, performance geek and SaaS startup founder). Miles and Tim recently got together to chat about lessons they’ve personally learned from leading real-world data migrations. You can watch the complete discussion here: Let’s look at three key takeaways from the chat. 1. Start with the Hardest, Ugliest Part First It’s always tempting to start a project with some quick wins. But tackling the worst part first will yield better results overall. Miles explains, “Start with the hardest, ugliest part first because you’re going to be wrong in terms of estimating timelines and noodling through who has the correct skills for each step and what are all of the edge conditions that drive complexity.” For example, he saw this approach in action during Google’s seven-year migration of the Gmail backend (handling trillions of transactions per day) from its internal Gmail data system to Spanner. First, Google built Spanner specifically for this purpose. Then, the migration team ran roll-forwards and roll-backs of individual mailbox migrations for over two years before deciding that the performance, reliability and consistency in the new environment met their expectations. Miles added, “You also get an emotional benefit in your teams. Once that scariest part is done, everything else is easier. I think that tends to work well both interpersonally and technically.” 2. Map the Minefield You can’t safely migrate until you’ve fully mapped out every little dependency. Both Tim and Miles stress the importance of exhaustive discovery: cataloging every upstream caller, every downstream consumer, every health check and contractual downtime window before a single byte shifts. Miles warns, “If you don’t have an idea of what the consequences of your change are…you’ll design a migration that’s ignorant of those needs.” Miles then offered a cautionary anecdote from his time at Twitter, as part of a team that migrated 362 petabytes of active data from bare-metal data centers into Google Cloud. They used an 800 Gbps interconnect (about the total internet throughput at the time) and transferred everything in 43 days. To be fair, this was a data warehouse migration, so it didn’t involve hundreds of thousands of transactional queries per second. Still, Twitter’s ad systems and revenue depended entirely on that warehouse, making the migration mission-critical. Miles shared: “They brought incredible engineers and those folks worked with us for months to lay out the plan before we moved any bytes. Compare that to something done a little more slapdash. I think there are plenty of places where businesses go too slow, where they overinvest in risk management because they haven’t modeled the cost-benefit of a faster migration. But if you don’t have that modeling done, you should probably take the slow boat and do it carefully.” 3. Engineer a “Blissfully Boring” Cutover “If you’re not feeling sleepy on cut-over day,” Miles quipped, “you’ve done something terribly wrong.” But how do you get to that point? Tim shared that he’s always found dual writes with single reads useful: you can switch over once both systems are up to speed. If the database doesn’t support dual writes, replicating writes via Change Data Capture (CDC) or something similar works well. Those strategies provide confidence that the source and target behave the same under load before you start serving real traffic. Then Tim asked Miles, “Would you say those are generally good approaches, or does it just depend?” Miles’ response: “I think the biggest driver of ‘It depends’ is that those concepts are generally sound, but real‐world migrations are more complex. You always want split writes when feasible, so you build operational experience under write load in the new environment. But sample architecture diagrams and Terraform examples make migrations look simpler than they usually are.” Another complicating factor: most companies don’t have one application on one database. They have dozens of applications talking across multiple databases, data warehouses, cache layers and so on. All of this matters when you start routing read traffic from various sources. Some systems use scheduled database-to-warehouse extractions, while others avoid streaming replication costs. Load patterns shift throughout the day as different workloads come online. That’s why you should test beyond the immediate reads after migration or when initial writes move to the new environment. So codify every step, version it and test it all multiple times – exactly the same way. And if you need to justify extra preparation or planning for migration, frame it as improving your overall high-availability design. Those practices will carry forward even after the cutover. Also, be aware that new platforms will inevitably have different operational characteristics…that’s why you’re adopting them. But these changes can break hard-coded alerts or automation. For example, maybe you had alerts set to trigger at 10,000 transactions per second, but the new system easily handles 100,000. Ensure that your previous automation still works and systematically evaluate all upstream and downstream dependencies. Follow these tips and the big day could resemble Digital Turbine’s stellar example. Miles shared, “If Digital Turbine’s database went down, its business went down. But the company’s DynamoDB to ScyllaDB migration was totally drama free. It took two and a half weeks, all buttoned up, done. It was going so well that everybody had a beer in the middle of the cutover.” Closing Thoughts Data migrations are always “high stakes.” As Miles bluntly put it, “I know that if I screw this up, I’ll piss off customers, drive them to competitors, or miss out on joint growth opportunities. It all comes down to trust. There are countless ways you can screw up an application in a way that breaches stakeholder trust. But doing careful planning, being thoughtful about the migration process, and making the right design decisions sets the team up to grow trust instead of eroding it.” Data migration projects are also great opportunities to strengthen your team’s architecture and build your own engineering expertise. Tim left us with this thought: “My advice for anyone who’s scared of running a data migration: Just have a crack at it. Do it carefully, and you’ll learn a lot about distributed systems in general – and gain all sorts of weird new insights into your own systems in particular. ” Watch the complete video (at the start of this article) for more details on these topics – as well as some fun “war stories.” Bonus: Access our free NoSQL Migration Masterclass for a deeper dive into migration strategy, missteps, and logistics.ScyllaDB Operator 1.19.0 Release: Multi-Tenant Monitoring with Prometheus and OpenShift Support

Multi-tenant monitoring with Prometheus/OpenShift, improved sysctl config, and a new opt-in synchronization for safer topology changes The ScyllaDB team is pleased to announce the release of ScyllaDB Operator 1.19.0. ScyllaDB Operator is an open-source project that helps you run ScyllaDB on Kubernetes. It manages ScyllaDB clusters deployed to Kubernetes and automates tasks related to operating a ScyllaDB cluster, like installation, vertical and horizontal scaling, as well as rolling upgrades. The latest release introduces the “External mode,” which enables multi-tenant monitoring with Prometheus and OpenShift support. It also adds a new guardrail in the must-gather debugging tool preventing accidental inclusion of sensitive information, optimizes kernel parameter (sysctl) configuration, and introduces an opt-in synchronization feature for safer topology changes – plus several other updates. Multi-tenant monitoring with Prometheus and OpenShift support ScyllaDB Operator monitoring uses Prometheus (an industry-standard cloud-native monitoring system) for metric collection and aggregation. Up until now, you had to run a fresh, clean instance of Prometheus for every ScyllaDB cluster. We coined the term “Managed mode” for this architecture (because, in that

case, ScyllaDB Operator would manage the Prometheus deployment):

ScyllaDB Operator 1.19 introduces the

“External mode” – an option to connect (one or

more) ScyllaDB clusters with a shared Prometheus deployment that

may already be present in your production environment:

The External mode provides a very important

capability for users who run ScyllaDB on Red Hat OpenShift. The

User Workload Monitoring (UWM) capability of OpenShift becomes

available as a backend for ScyllaDB Monitoring:

Under the hood, ScyllaDB Operator 1.19 implements the new

monitoring architectures by extending the

ScyllaDBMonitoring CRD with a new field

.spec.components.prometheus.mode that can now be set

to Managed or External.

Managed is the preexisting behavior (to deploy a

clean Prometheus instance), while

External deploys just the Grafana dashboard using

your existing Prometheus as a data source instead, and puts

ServiceMonitors and PrometheusRules

in place to get all the ScyllaDB metrics there. See the new

ScyllaDB Monitoring overview and

Setting up ScyllaDB Monitoring documents to learn more about

the new mode and how to set up ScyllaDB Monitoring

with an existing Prometheus instance. The

Setting up ScyllaDB Monitoring on OpenShift guide offers

guidance on how to set up

User Workload Monitoring (UWM) for ScyllaDB in OpenShift. That

being said, our experience shows that cluster administrators prefer

closer control over the monitoring stack than what the

Managed mode offered. For this reason, we intend to

standardize on using External in the long run.

So, we’re still supporting the Managed mode, but it’s

being deprecated and will be removed in a future Operator version.

If you are an existing user, please consider deploying your own

Prometheus using the Prometheus

Operator platform guide and switching from Managed

to External. Sensitive information excluded from

must-gather ScyllaDB Operator comes with an embedded tool (called

must-gather) that helps preserve the configuration

(Kubernetes objects) and runtime state (ScyllaDB node logs, gossip

information, nodetool status, etc.) in a convenient

archive. This allows comparative analysis and troubleshooting with

a holistic, reproducible view. As of ScyllaDB Operator 1.19,

must-gather comes with a new setting

--exclude-resource that serves as an additional

guardrail preventing accidental inclusion of sensitive information

– covering Secrets and SealedSecrets by default. Users can specify

additional types to be restricted from capturing, or override the

defaults by setting the --include-sensitive-resources

flag. See the

Gathering data with must-gather guide for more information.

Configuration of kernel parameters (sysctl) ScyllaDB nodes require

kernel parameter (sysctl) configuration for optimal performance and

stability – ScyllaDB Operator 1.19 improves the API to do that.

Before 1.19, it was possible to configure these parameters through

v1.ScyllaCluster‘s .spec.sysctls.

However, we learned that this wasn’t the optimal place in the API

for a setting that affects entire Kubernetes nodes. So, ScyllaDB

Operator 1.19 lets you configure sysctls through

v1alpha1.NodeConfig for a range of Kubernetes nodes at

once by matching the specified placement rules using a label-based

selector. See the

Configuring kernel parameters (sysctls) section of the

documentation to learn how to configure the sysctl values

recommended for production-grade ScyllaDB deployments. With the

introduction of sysctl to NodeConfig, the legacy way of configuring

sysctl values through v1.ScyllaCluster‘s

.spec.sysctls is now deprecated. Topology change

operations synchronisation ScyllaDB

requires that no existing nodes are down when a new node is added

to a cluster. ScyllaDB Operator 1.19 addresses this by

extending ScyllaDB Pods for newly joining nodes with a barrier

blocking the ScyllaDB container from starting until the

preconditions for bootstrapping a new node are met. This feature is

opt-in in ScyllaDB Operator 1.19. You can enable it by setting the

--feature-gates=BootstrapSynchronisation=true

command-line argument to ScyllaDB Operator. This feature supports

ScyllaDB 2025.2 and newer. If you are running a multi-datacenter

ScyllaDB cluster (multiple ScyllaCluster objects bound

together with external seeds), you are still required to verify the

preconditions yourself before initiating any topology changes. This

is because the synchronisation only occurs on the level of an

individual ScyllaCluster. See

Synchronising bootstrap operations in ScyllaDB for more

information. Other notable changes Deprecation of

ScyllaDBMonitoring components’ exposeOptions By adding support for

external Prometheus instances, ScyllaDB Operator 1.19 makes a step

towards reducing ScyllaDBMonitoring‘s complexity

by deprecating exposeOptions in both

ScyllaDBMonitoring‘s Prometheus and Grafana

components. The use of exposeOptions is limited

because it provides no way to configure an Ingress that will

terminate TLS, which is likely the most common approach in

production. As an alternative, this release introduces a more

pragmatic and flexible approach: You can simply document how the

components’ corresponding Services can be exposed. This gives you

the flexibility to do exactly what your use case requires. See the

Exposing Grafana documentation to learn how to expose Grafana

deployed by ScyllaDBMonitoring using a

self-managed Ingress resource. The deprecated

ScyllaDBMonitoring‘s exposeOptions will

be removed in a future Operator version. Dependency updates This

release also includes regular updates of ScyllaDB Monitoring and

the packaged dashboards to support the latest ScyllaDB releases

(4.11.1->4.12.1, #3031),

as well as its dependencies: Grafana (12.0.2->12.2.0) and

Prometheus (v3.5.0->v3.6.0). For more changes and details, check

out the GitHub

release notes. Upgrade instructions For instructions on

upgrading ScyllaDB Operator to 1.19, see the

Upgrading Scylla Operator documentation. Supported versions

ScyllaDB 2024.1, 2025.1 – 2025.3 Kubernetes 1.31 – 1.34 Container

Runtime Interface API v1 ScyllaDB Manager 3.5, 3.7 Getting started

with ScyllaDB Operator ScyllaDB Operator

Documentation Learn

how to deploy ScyllaDB on Google Kubernetes Engine (GKE)

Learn

how to deploy ScyllaDB on Amazon Elastic Kubernetes Engine

(EKS) Learn how

to deploy ScyllaDB on a Kubernetes Cluster Related links

ScyllaDB Operator source (on

GitHub) ScyllaDB Operator image on

DockerHub ScyllaDB Operator

Helm Chart repository ScyllaDB Operator documentation

ScyllaDB Operator for Kubernetes

lesson in ScyllaDB University Report a

problem Your feedback is always welcome! Feel free to open an

issue or reach out on the #scylla-operator channel in ScyllaDB User Slack. Instaclustr product update: December 2025

Instaclustr product update: December 2025Here’s a roundup of the latest features and updates that we’ve recently released.

If you have any particular feature requests or enhancement ideas that you would like to see, please get in touch with us.

Major announcements OpenSearch®AI Search for OpenSearch®: Unlocking next-generation search

AI Search for OpenSearch, which is now available in Public Preview on the NetApp Instaclustr Managed Platform, is designed to bring semantic, hybrid, and multimodal search capabilities to OpenSearch deployments—turning them into an end-to-end AI-powered search solution within minutes. With built-in ML models, vector indexing, and streamlined ingestion pipelines, next-generation search can be enabled in minutes without adding operational complexity. This feature powers smarter, more relevant discovery experiences backed by AI—securely deployed across any cloud or on-premises environment.

ClickHouse®

FSx for NetApp ONTAP and Managed ClickHouse® integration is now

available

We’re excited to announce that NetApp has introduced seamless

integration between Amazon FSx for NetApp ONTAP and Instaclustr

Managed ClickHouse, to enable customers to build a truly hybrid

lakehouse architecture on AWS. This integration is designed to

deliver lightning-fast analytics without the need for complex data

movement, while leveraging FSx for ONTAP’s unified file and object

storage, tiered performance, and cost optimization. Customers can

now run zero-copy lakehouse analytics with ClickHouse directly on

FSx for ONTAP data—to simplify operations, accelerate

time-to-insight, and reduce total cost of ownership.

Instaclustr for PostgreSQL® on Amazon FSx for ONTAP: A new

era

We’re excited to announce the public preview of Instaclustr Managed

PostgreSQL integrated with Amazon FSx for NetApp ONTAP—combining

enterprise-grade storage with world-class open source database

management. This integration is designed to deliver higher IOPS,

lower latency, and advanced data management without increasing

instance size or adding costly hardware. Customers can now run

PostgreSQL clusters backed by FSx for ONTAP storage, leveraging

on-disk compression for cost savings and paving the way for

ONTAP-powered features, such as instant snapshot backups, instant

restores, and fast forking. These ONTAP-enabled features are

planned to unlock huge operational benefits and will be launched

with our GA release.

- Released Apache Cassandra 5.0.5 into general availability on the NetApp Instaclustr Managed Platform.

- Transitioned Apache Cassandra v4.1.8 to CLOSED lifecycle state; scheduled to reach End of Life (EOL) on December 20, 2025.

- Kafka on Azure now supports v5 generation nodes, available in General Availability.

- Instaclustr Managed Apache ZooKeeper has moved from General Availability to closed status.

- Kafka and Kafka Connect 3.1.2 and 3.5.1 are retired; 3.6.2, 3.7.1, 3.8.1 are in legacy support. Next set of lifecycle state changes for Kafka and Kafka Connect in end March 2026 will see all supported versions 3.8.1 and below marked End of Life.

- Karapace Rest Proxy and Schema Registry 3.15.0 are closed. Customers are advised to move to version 5.x.

- Kafka Rest Proxy 5.0.0 and Kafka Schema Registry 5.0.0, 5.0.4 have been moved to end of life. Affected customers have been contacted by Support to schedule a migration to a supported version as soon as possible.

- ClickHouse 25.3.6 has been added to our managed platform in General Availability.

- Kafka Table Engine integration with ClickHouse has added support to enable real-time data ingestion, streamline streaming analytics, and accelerate insights.

- New ClickHouse node sizes, powered by AWS m7g, r7i, and r7g instances, are now in Limited Availability for cluster creation.

- Cadence is now available to be provisioned with Cassandra 5.x, designed to deliver improved performance, enhanced scalability, and stronger security for mission-critical workflows.

- OpenSearch 2.19.3 and 3.2.0 have been released to General Availability.

- PostgreSQL AWS PrivateLink support has been added, enabling connectivity between VPCs using AWS PrivateLink.

- PostgreSQL version 18.0 has now been released to General Availability, alongside PostgreSQL version 16.10, 17.6.

- Added new PostgreSQL metrics for connect states and wait event types.

- PostgreSQL Load Balancer add-on is now available, providing a unified endpoint for cluster access, simplifying failover handling, and ensuring node health through regular checks.

- We’re working on enabling multi-datacenter (multi-DC) cluster provisioning via API and console, designed to make it easier to deploy clusters across regions with secure networking and reduced manual steps.

- We’re working on adding Kafka Tiered Storage for clusters running in GCP— designed to bring affordable, scalable retention, and instant access to historical data, to ensure flexibility and performance across clouds for enterprise Kafka users.

- We’re planning to extend our Managed ClickHouse to allow it to work with on-prem deployments.

- Following the success of our public preview, we’re preparing to launch PostgreSQL integrated with FSx for NetApp ONTAP (FSxN) into General Availability. This enhancement is designed to combine enterprise-grade PostgreSQL with FSxN’s scalable, cost-efficient storage, enabling customers to optimize infrastructure costs while improving performance and flexibility.

- As part of our ongoing advancements in AI for OpenSearch, we are planning to enable adding GPU nodes into OpenSearch clusters, aiming to enhance the performance and efficiency of machine learning and AI workloads.

- Self-service Tags Management feature—allowing users to add, edit, or delete tags for their clusters directly through the Instaclustr console, APIs, or Terraform provider for RIYOA deployments.

- Cadence Workflow, the open source orchestration engine created by Uber, has officially joined the Cloud Native Computing Foundation (CNCF) as a Sandbox project. This milestone ensures transparent governance, community-driven innovation, and a sustainable future for one of the most trusted workflow technologies in modern microservices and agentic AI architectures. Uber donates Cadence Workflow to CNCF: The next big leap for the open source project—read the full story and discover what’s next for Cadence.